How to make 'smart' cities work for everyone

- 9 minsLast week I gave a lunchtime lecture at the Open Data Institute Queensland (ODIQ). Below is a rough sketch of what I said. You can find slides here.

This post originally appeared on the ODI Queensland website.

When Maree (CEO of ODIQ) asked me to send through a summary for this lunchtime lecture, it was the day after Donald Trump won the US election.

We’d agreed on smart cities as a theme weeks in advance. That day, surfing waves of commentary and trying to understand the trends that shaped that election, I wondered whether smart cities were being designed for the benefit of all citizens or only a few.

Today I want to recast the smart cities narrative to place people - not technology - at its centre. I want to talk about the benefits of data and openness: open data, open source, open standards. And I want to reflect on the human experience of smart city solutions.

In this talk I ask myself three questions:

- What makes a city ‘smart’?

- What role does data play in a smart city?

- Are we empowering or dividing people?

What is a ‘smart’ city?

I’m going to start with some definitions because they shape how a policy maker or an organisation approaches smart city planning and investment. There’s lots of definitions out there, but we’re only looking at a few today.

The global industry coalition Smart City Council says that a smart city:

Uses information and communications technology (ICT) to enhance its livability, workability and sustainability.

I don’t like this one because it leads with technology. To me, it implies that ICT will always help, regardless of its application or the problem at hand.

I’ve been looking around for an Australian approach to ‘smart cities’. The Federal Government doesn’t have an explicit definition of a ‘smart city’, but there’s an indication of how it approaches the term in its 2016 Smart City Strategy. Its goals are:

- Becoming smarter investors in our cities’ infrastructure

- Coordinating and driving smarter city policy

- Driving the uptake of smart technology, to improve the sustainability of our cities and drive innovation

You don’t really get a feel for what a good ‘smart’ city looks like in the Strategy. There’s still a lot of focus on investment in smart technology being by itself a good thing for cities.

There are many great examples of data and digital being used effectively in cities. But for a policy maker about to embark on their own smart cities strategy, starting with technology encourages a disconnect from the broader challenges and priorities facing a council or government.

Making big investments in new technologies and data doesn’t necessarily mean cities are better off - it’s how they are used that creates impact.

The Open Data Institute describes a smart city as an ‘open city’,

Putting people and openness at the heart of its design and operation.

I like that it emphasises people at the core of smart city planning. We’ll talk about open data and openness as part of city planning a little later on.

This definition from the UK Department of Business, Innovation & Skills is good too:

A Smart City should enable every citizen to engage with all the services on offer, public as well as private, in a way best suited to his or her needs.

It’s citizen-oriented and recognises that people have different needs. Not everyone is online and not all solutions are digital ones.

Ultimately, a smart city is one that aims to improve the lives of its citizens. A good smart city strategy considers the challenges and opportunities facing its community, and explores ways new technologies and data might help to respond to them. Technology might help you get to a solution; it’s not a solution in itself.

How new technologies and data are contributing to ‘smarter’ cities

Having access to more data, and better tools to collect and analyse data, is changing the way we make decisions and deliver services. ‘Big data’, the Internet of Things and machine learning are some of the developments in the sights of policy makers.

From smart parking to remote monitoring of the infirm and elderly, sensors are changing the way we plan city infrastructure.

Better use of data is helping to design new services, like hubs for commuters to work closer to home.

Some smart city solutions don’t involve new technologies and data at all. They can be about retrofitting old technologies for a new purpose, like turning retired diesel buses into portable showers for a city’s homeless population.

Not all smart city initiatives need to involve an app, a sensor or a chatbot. Different people have different needs. When evaluating smart city ideas, how people engage with information and where they go to find it needs to be taken into account. You can invest a lot of money in ‘smart’ infrastructure while forgetting about the citizen, resulting in little to no impact.

Building open city data infrastructure

The Open Data Institute describes data as infrastructure. Just as roads help you navigate to a location, data helps you make a decision.

Sometimes cities make investments in new data technologies and sources (e.g. from sensors) without taking into account the health of their underlying data infrastructure. Having an understanding of the data assets you need to deliver your services (private sector or public sector); clear responsibilities and expectations of organisations managing that data; and guidelines and policies to shape its use, is important.

Openness - open data, open standards, open source, open collaboration - is helping to build new services for citizens at scale. Cities and councils are starting to open up data for organisations and innovators to explore, and generate new business models. In the UK, opening up government data is estimated to contribute an additional 0.5% to GDP annually.

CityMapper, the journey planner app that originated in London (now in cities around the world, including Melbourne and Sydney) has described open data as the essential backbone for its service. It’s being used to provide new ways of engaging with government, and helping people find their nearest public toilet.

The human experience of smart cities

Not everyone accesses information the same way you do. In Australia 86% of households have the internet at home. With a population of over 24 million, that’s around 3.3 million people who aren’t online at home.

And while new technologies and data are helping to make services more efficient and automated, they’re also impacting on peoples’ jobs. Using e.g. drones to conduct site inspections will be safer and faster, but in the short term it will impact machinery and equipment providers and site inspectors. We’re going to see things like taxi and Uber drivers replaced by automated cars.

The impacts of automation are being studied and policies being developed to create new jobs. Being mindful of ways in which your citizens might be adversely affected by ‘smart’ solutions is part of city planning.

But data and digital can also empower and connect people together.

Open data is helping people engage with their community in unexpected ways. In Leeds, two developers and composers used open footfall data to create a musical score - and it’s really beautiful. Open data is also being incorporated into jewellery, art and even video games.

I’m always excited to see ‘smart city’ ideas that are trying to bring people together. I was just introduced to ParkRun in Australia, which organises free weekly runs for anyone and everyone - a great way to meet new people. A startup idea in the UK called Rabble aims to connect families with communal volunteering projects.

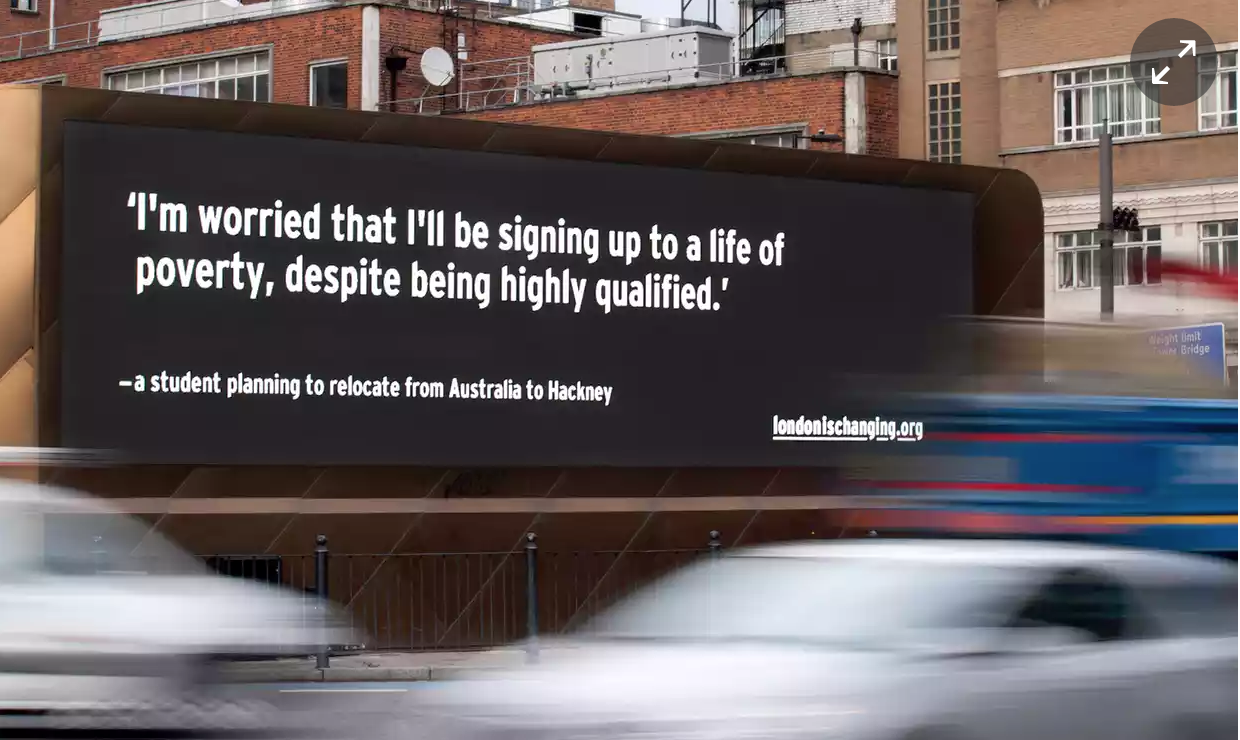

Sometimes technology can bring you into contact with experiences you might not otherwise be aware of. A 2015 London project called London is Changing projected comments from people about their experiences of housing in London onto billboards in the inner city.

Planning your smart city initiative

I’ve ranged across a few topics today. I’m still working out what a more people centric approach to smart cities might look like, and how to articulate it.

To summarise:

- Lead with citizen needs - not new technologies. Your smart city initiative should be driven by the challenges and opportunities already facing your citizens. Connect it to other policies, link things together.

- Evaluate your data infrastructure - assets, technology, skills, governance. To make best use of new data sources and tools, you’ll need a robust foundation to build on.

- Invest in open - open data, open source, open standards, open collaboration. It helps make things better, faster, and cheaper.

- Be mindful - of impact, of how you deliver, of privacy and ethics. Design solutions that can be delivered, and be prepared for impacts both positive and negative. I barely touched on privacy in this talk but it’s an important area for policy makers to get into.

I hope we’re finishing up feeling like there’s more to smart cities than a beautiful website or a shiny app. The technology or data by itself is of limited value; it’s what you do with it to ultimately change peoples’ lives for the better.

Hopefully you’re leaving here with lots to think about: a little wiser, a little ‘smarter’ and excited by the possibilities.